Abstract

In the recent judgment of Tiger Pictures Entertainment Ltd (“Tiger Pictures”) v. Encore Films Pte Ltd (“Encore Films”)[1], the General Division of the High Court of Singapore determined that Encore Films, a Singapore-incorporated company that distributes films, had infringed Tiger Pictures’ copyright of the highly successful Chinese film “Moon Man”. This conclusion was reached on the basis that no valid contract permitting use of the film had ever been reached through WeChat and E-mail negotiations.

Despite recognizing that chat records can, in principle, form a contract, the High Court of Singapore decided the case based primarily on the lack of two key factors leading to a failure of contract formation. These were, on the facts of the particular case, the absence of an intention to create legal relations through the relevant WeChat and E-mail negotiations, and the uncertainty as to the contract’s core terms.

Case Background

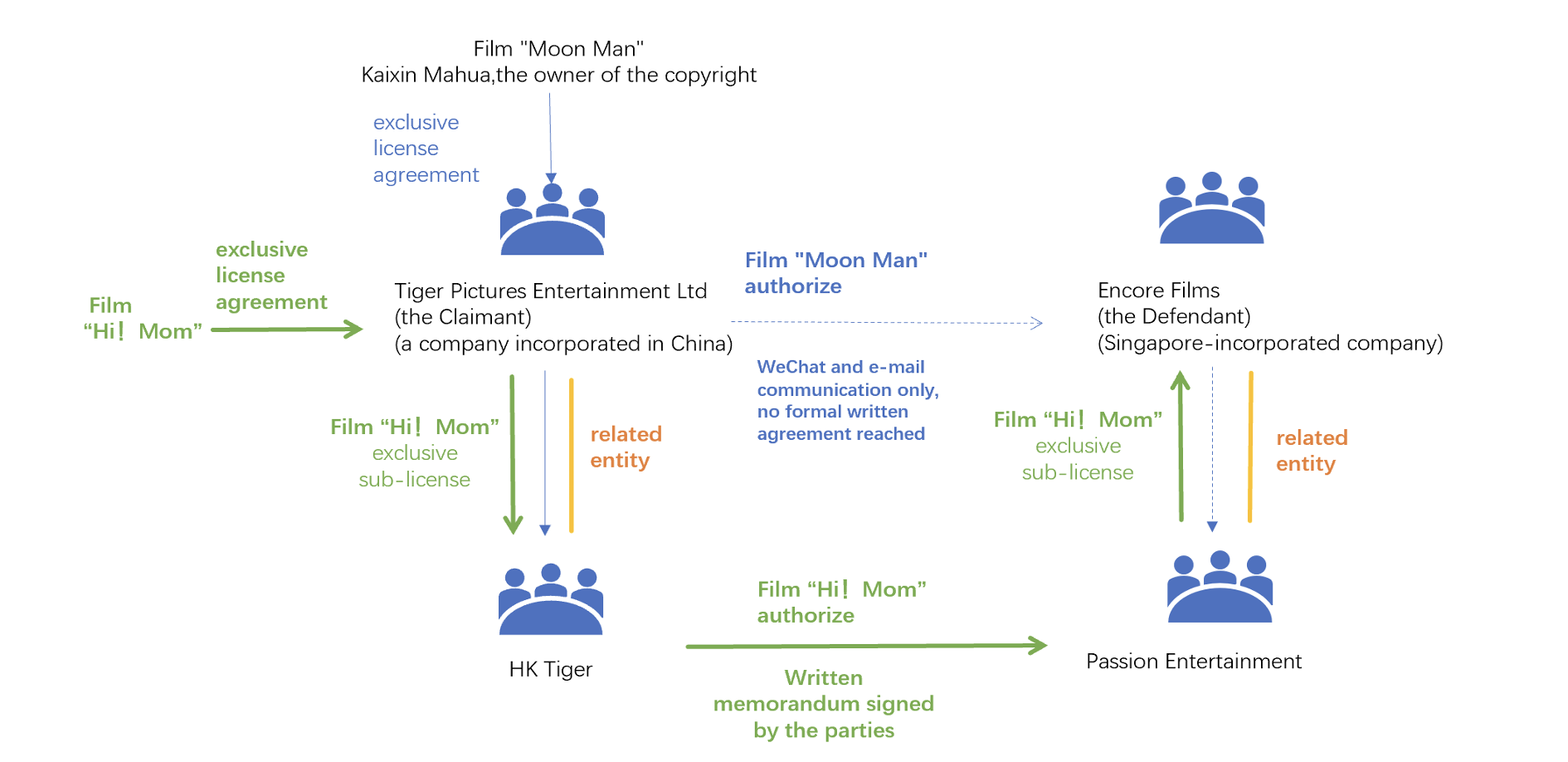

On 19 August 2022, Kaixin Mahua, the Chinese copyright owner of “Moon Man” (the “Film”), exclusively licensed the Film to Tiger Pictures, which then sub-licensed it to HK Tiger. Afterwards, Tiger Pictures’ President, Mr. Young, discussed distributing the film in Singapore with Encore Films’ Managing Director, Ms. Lee, via WeChat and E-mail. Despite some issues with the plan as to the promotion and advertising of the Film, Tiger Pictures and HK Tiger sent Encore Films the digital cinema package for the Film on 22 August 2022. Drafts of the distribution agreement were then exchanged between 31 August and 7 September 2022, but no consensus was reached.

On 8 September 2022, Tiger Pictures and HK Tiger warned Encore Films against exhibitions of the Film without a signed agreement, though Encore Films was still permitted to organize the Sneak Sessions. On 13 September 2022, Encore Films claimed a contract had been formed on 20 August 2022, and made arrangements to release the Film for general screening in Singapore on 15 September 2022. On that date, Encore Films screened the Film in cinemas, taking no heed of the warnings from Tiger Pictures’ lawyers that no agreement for the theatrical release, except for Sneak Sessions.

Tiger Pictures then sued Encore Films for copyright infringement. Encore Films defended that an agreement had been made through WeChat and E-mail negotiations (the “Alleged Agreement”).

Key Points of the Judgment

In determining whether Encore Films had infringed Tiger Films’ copyright, Justice Dedar Singh Gill focused on whether an effective distribution agreement for the Film was established. The court found that no valid distribution agreement had been reached between the parties, based on the following key considerations:

1. Whether the parties intended for the WeChat and E-mail Negotiations to create legal relations?

The parties did not intend the WeChat and E-mail negotiations to create legal relations, as both parties aimed to sign a written contract. This was in turn evidenced by the defendant’s notification to the claimant that its staff would send a written contract for execution.

The terms of the Alleged Agreement also evidence a lack of intention to create legal relations. There is an interplay between the contractual formation requirements of an intention to create legal relations and certainty. Generally, where parties have entered into a signed agreement that adequately sets out the essential terms of the transaction, the court would be extremely reluctant to infer that the parties had not intended to be bound. Conversely, uncertain and incomplete terms are often viewed as strong evidence of a lack of contractual intent, especially when key terms such as (1) the identity of the distribution company, (2) the need for a promotions and advertising plan and related receipt, (3) the scope of licensed rights and (4) the license period were not agreed upon.

The parties’ prior dealings in relation to the “Hi! Mom” film reinforced this position. In previous transactions, both parties had executed the transaction terms in the form of a written memorandum in addition to the discussions on WeChat and E-mail. This established a precedent between the parties that a written form for a contract was required.

Furthermore, the parties’ subsequent conduct does not contradict the lack of intention to create legal relations. Although Encore Films claimed to have started contract preparations after believing that the contract was formed and argued that Tiger Pictures’ lack of objection should be seen as an acknowledgment of the contract, there was no evidence that Tiger Pictures was aware or should have been aware of Encore Films’ preparations. Therefore, subsequent actions could not overturn the lack of intention to create legal relations through WeChat and E-mail.

2. Whether the Alleged Agreement fails for lack of certainty?

Certainty and completeness are requirements for a valid contract. Even if there is a valid offer and acceptance, a contract may still fail due to uncertainty and incompleteness. For a binding contract to arise, the parties must agree on all essential terms. In this case, the parties did not agree on the core terms of the Film distribution agreement, leading the court to conclude that the alleged contract did not meet the certainty requirement and that no valid agreement was reached.

In summary, the parties had not reached a valid agreement for the distribution of the Film given the lack of intention to establish legal relations through the WeChat and E-mail negotiations, and the lack of certainty in the Alleged Agreement. Therefore, the court ruled that Encore Films had infringed on Tiger Pictures’ copyright over the Film.

Comment

In cross-border transactions, understanding the contractual formation requirements and validity regulations of China and its key trading partners (such as Singapore, the U.S., and the U.K.) can effectively reduce obstacles to commercial cooperation, thereby minimizing the likelihood of disputes. With the widespread use of social media, platforms like WeChat and WhatsApp are commonly used for business communications. Can courts in various countries recognize social media chat records as legally binding contracts? If so, what requirements must be met for WeChat messages to form a contract?

The rules for contract formation and validity are similar across the major legal systems. WeChat and similar social media chat records can form contracts in such jurisdictions, subject of course to the particular facts of the case. Under Chinese law, Article 469 of the 2020 Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China and Article 3 of the 2005 Electronic Signature Law of China establish the principle of freedom of contract, with few exceptions requiring specific forms or conditions for contract formation. The Supreme People’s Court also recognized WeChat as merely a communication tool during contract formation, indicating that there was no fundamental difference between contracts formed through WeChat and traditional written contracts.[2]

Similarly, in this case, the Singapore court also acknowledged the potential of WeChat messages to form a valid contract. This formed the basis for Dedar Singh Gill J going further to hear the substantive contents.

As for the U.S., a text message can also be legally binding under the 2000 Electronic Signatures Global and National Commerce Act, or E-Sign Act for short. According to the E-sign Act, “(1) a signature, contract, or other record relating to such transaction may not be denied legal effect, validity, or enforceability solely because it is in electronic form; and (2) a contract relating to such transaction may not be denied legal effect, validity, or enforceability solely because an electronic signature or electronic record was used in its formation.”[3] In cases such as Stanley Works Israel Ltd. v. 500 Grp. Inc.,[4] and Spilman v. Matyas,[5] U.S. courts have also recognized that electronic exchanges can constitute legally binding agreements.

Regarding the essential elements a valid contract must include, the requirements are the same for both traditional written contracts and electronic ones:

(a) Offer and acceptance – one party must make an offer that another party accepts;

(b) Consideration – both parties must engage in a valuable exchange, such as one party providing services and the other party paying for those services. (This element is not required under Chinese law but is considered a key point under UK and US law.);

(c) Intent to be bound – both parties must intend the messages to create a legally binding agreement; and

(d) Mutual assent – both parties have a mutual understanding and agreement on the essential terms of the contract.

Finally, some guidance on utilizing chat tools (WeChat, WhatsApp, etc.) during business negotiations is as follows. If there is no intention to form a contract during informal communications:

(a) it is crucial to explicitly state that the discussions are non-binding, clarifying that communications are for negotiating / information purposes only and do not constitute a contract or legal commitment.

(b) confirming specific contract terms in a formal written agreement is essential to ensure clarity and avoid misunderstandings.

(c) using non-binding language, such as “discussion” or “proposal” instead of “contract” or “commitment,” can help prevent accidental commitments.

(d) implementing company policies and providing training for employees on these practices further safeguards against unintentional contract formation.

Conversely, if the intention is to form a contract through social media or messaging applications, ensure that communications meet the above-mentioned elements for contract formation. In significant business negotiations, involve lawyers early on to meet company intentions and achieve desired business outcomes through WeChat communications.

[1] [2024] SGHC 39

[2] (2023) Supreme People's Court Civil Jurisdiction 134

[3] Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act, 15 U.S.C. §7001 (2000). S.101(a).

[4] Stanley Works Isr. Ltd. v. 500 Grp., Inc., 332 F. Supp. 3d 488 (D. Conn. 2018)

[5] Spilman v. Matyas, 212 A.D.3d 859, 183 N.Y.S.3d 473, 2023 N.Y. Slip Op. 344 (N.Y. App. Div. 2023)